Joshua and Judges are the first two books of the Hebrew Bible dealing with the beginnings of Israel’s existence in the land they understood God had promised them. Partly invaders into territories not originally belonging to them, partly allies with original inhabitants of the land, by the end of Joshua they have managed to gain an uncertain foothold in the land of Canaan. The book of Judges shows how fragile their initial existence was during the first centuries, as they are constantly beset by opponents from outside and inside the land.

In today’s world, the issue of borders, of insiders and outsiders, is one of the most important social and political realities impinging on our reality. Who belongs and who is judged not to belong, who has a right to which space, who can be deprived of basic human rights because they do not belong? These are acute questions because of the forced emigration of multitudes of peoples. To these questions Joshua and Judges provide far more complicated answers than one might expect. The material in these texts can be used for the purpose of land grabs, nation building, and validating one group of people’s superiority over another. It has been so used in the United States and elsewhere as I point out in the Introduction under the heading The Long Arm of the Past. But biblical text has a habit of eluding our grasp and providing insight where we might not expect to find it.

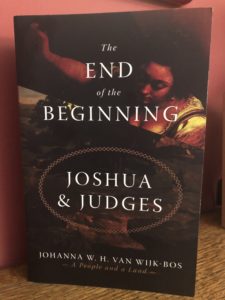

When I wrote this book, the first of three volumes of commentary on Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings, called A People and a Land, I thought I knew the material pretty well. I had been a teacher of Hebrew Bible in one of our Presbyterian Seminaries for 40 years after all. The one thing I learned in the course of my career of teaching and writing, however, is that there is always more to learn about the biblical text and that we never come to the end of the many voices that speak in it. What I thought I knew turned to be founded on shaky ground and the text of Joshua especially surprised me by the many times that the idea of a “total conquest” turns out to consist of frayed fabric. The overriding ethic of the Torah of care and love for the stranger has a place here also, even in the midst of the tumult of war.

I worry that knowledge of the biblical text, especially of the Hebrew Bible, is disappearing in our mainline Christian denominations. I have written also out of a desire to reacquaint people with this material. Judges contains some of the best stories that come to us from this ancient world, with larger-than-life flawed heroes. Especially important is how the stories depict women in roles that will amaze us. For all that the ancient Israelite society was organized along patriarchal principles,, the text does not give evidence of the patriarchal ideologies that dominate today’s world. As a feminist Christian scholar I pay close attention to the places where women are present in the text and to their function. They appear in Judges in the role of judge, warrior, assassin, text composer, prostitute, as well as the more traditional one of mother. These are rich stories that we forget to our loss.

There is also great violence depicted in the narratives, also violence against women. We can look at the story of Jefta’s daughter or the concubine in Gibeah in Judges and read them as if looking in a mirror. They drive us to ask immensely important questions about the progress we have or have not made in our world dominated by patriarchal practices and ideologies, where women all too often survive in a personal war-zone.

In writing about the texts in the Historical books I am conscious of the fact that they were collected in the aftermath of the trauma of war. While much of the material may have been available already in written form before the Babylonian exile, they were not edited and put into the present collection until afterwards. The trauma created by war put its stamp on the entire compilation. It tells the people’s history in story and song in order to recount the past but also in order to find a way forward. Those who suffer from the trauma of war tell their stories to see in the dark. As a child of war myself this aspect of the material speaks strongly to me, and I recount some of my personal experience in the Introduction to this volume. My hope is that the readers of this book will enter into these texts of the Bible willing to be surprised rather than knowing ahead of time what they have to offer. The text does not provide any kind of blueprint; we need to engage with it at the point of the most important ethical questions facing us in today’s world. Sometimes our engagement will only raise more questions, but sometimes it may lead us to find a way forward as it may have done for the small fragile community that created it.