Artemisia Gentileschi was a painter in the first half of the sixteenth century, one of many women painters of the period, with a phenomenal output. She painted both biblical and secular subjects. Of the biblical images, Judith’s beheading Holofernes, Suzanna and the Elders, and Yael about to dispatch Sisera (see above) are perhaps the best known. Students and I saw some of her paintings seven years ago in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, when I taught a class on the Bible and Art in the Renaissance. Gentileschi was a bit later than our period but she was too good to pass up. Her paintings are dispersed throughout the world, in Budapest, where you can find the one of Yael and Sisera, in Naples and in Detroit, but we managed to find some of hers tucked away after what seemed an endless walk through the Gallery. You can locate them online under her name.

To say that these portrayals may be “the best known” of Gentileschi’s work is overstating the case, for she is not exactly a household name. Somewhat restored to memory by the Italian art critic Roberto Longhi in 1910, he referred to her as “the only woman in Italy who ever knew about painting, coloring and other fundamentals,” (https://www.wantedinrome.com/news/artemisia-gentileschi-tragedy-and-triumph.html). This declaration revealed Longhi’s condescension and ignorance, as he discounted all the other women painters of the Renaissance and early Baroque periods.. Lifting up one woman erased a host of others. His posture was also a testimony to the habitual erasure of women in recorded historical memory instead of paying attention to their actual contributions.

Gentileschi finally received true recognition with a major exhibition in 2016-17 in the Palazzo Braschi in Rome. Far from the “only woman in Italy who knew anything about painting,” she was in fact joined by many women visual artists of the period in Italy and elsewhere, who were not only productive but famous in their time. At the exhibit in Rome, 29 of her paintings were joined by 66 works of contemporaries. In checking the website I noticed the absence among these contemporaries of the names of, for example, Lavinia Fontana, the splendid Sofonisba Anguissola, or Artemisia’s predecessor Plautilla Nelli. These are only a few of the names I could mention. At my most recent count I found 30 women painters of the late Renaissance and Baroque period mostly in Italy, expanding to 40 when I looked further afield, to the Low Countries, England and France. You really don’t have to look that far to find them today on the internet; persistence and a little time will get you there.

The Renaissance was one of those times when the ferment of the period opened the door to women to enter into a world in which they had heretofore only had a rare presence. Not only were they present, they found find acceptance, appreciation and fame. Afterwards, patriarchal and misogynist mindsets of later eras erased them from public memory. Erasure of women’s contributions in all fields, whether in past or present, must be unmasked wherever we find it. The world-famous art historian Giorgio Vasari was not a “feminist” because he included four women in his “Lives.” He named them because he could hardly avoid doing so. While he names Properzia de Rossi, Plautilla Nelli, Sofonisba Anguissola, and Madonna Lucrezia, he also had the examples of Antonia Ucello, Barbara Ragnori, and his contemporaries , Lucia,Anguissola, Barbara Longhi, and Dana Scultori Ghisi, to name a few. It speaks volumes for author and art historian Noah Charney to call Vasari feminist and to observe that until the 20th century “crafts, like painting and sculpture, were a man’s job almost exclusively.” and that “women of the Renaissance were usually nuns, wives and mothers, prostitutes, etc.” (https://observer.com/2017/01/the-forgotten-women-artists-of-the-renaissance-and-the-man-who-championed-them/).

Recognition of Artemisia Gentileschi in the tradition of women painters is important. It is also important to remember her in the context of a period when the door for women opened to a world of possibilities beyond traditional expected roles as “nuns, mothers and prostitutes.” When Gentileschi is defined as the “only woman” painter of her time, making her the exception and an outlier, this recognition is established at the cost of ignoring her talented and productive sister artists. Also, erasing the memory of women’s presence in a male dominated field of the past discourages participation in present times. If we cannot find ourselves by looking at the past it is going to be difficult to take on non-traditional roles in the present. A door that is wide open can become a door ajar and then a door that closes altogether. We do well to keep this in mind today. Vigilance in preserving her memory and that of the multitude of women who contributed to the visual arts through the centuries is always in order.

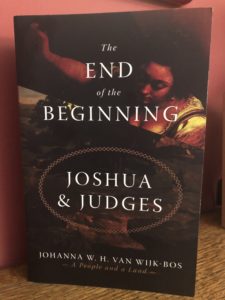

The choice of my publisher’s design team to put Gentileschi’s Yael and Sisera on the cover of the first book in my three-volume series A People and a Land, is a cause for celebration. We also celebrate all her sister artists of the period and beyond. Her painting shows a traditional interpretation of the moment before Yael murders Sisera with her tent-peg. If you are a part of a community that inherited the stories of the Bible, you may know the story of Yael and Sisera; or you may think you know it. Yael too was not alone in her time, but joined in spirit with her sister Deborah, a poet and prophet, a soldier who fought at the side of her general. You can read my take on both women in: